Russia’s Cyber-crime Industry

10 May 2017

In today’s world of technology almost every activity is now conducted or monitored online. Individuals commit transactions, share documents, and communicate across continents seemingly instantaneously. As there are personal and confidential information available online, there are those who are willing to illegally obtain that information. While cyber-crimes are committed from all parts of the world, the focus on his report will be the cyber-criminal activities occurring in Russia. This paper will analyze the types of cyber-crimes traced to Russians, the organization of the criminals, and its growth market.

Types of Russian Cyber-crime Threats

There are different types of activities that are classified as cyber-crimes in which hackers in Russia are known to engage in. According to Paolo Satori, a Commissioner at Interpol in Romania, the activities seen in Russia include “email spam, child pornography, fraud and phishing, cyber extortion, disclosure of personal and confidential data, compromise of resources and web defacements, compromise network systems and websites, denial of service, and unlawful e-commerce and services” (Gertz 2015). There is also digital ‘kompromat’, a type of social assassination where illegal documents or false information gets pushed onto the victim’s computer or linked to the victim’s accounts, discrediting the victim, changing public opinion, and even leading to the victim being arrested (Higgins 2016).

Cyber extortion is one of the most popular types of crime, due to the fee demanded to restore the hijacked computer network is normally cheaper than having the problem repaired, and faster, with less risk of losing customers, so companies are generally willing to pay the ransom (Gertz 2015). The devices in which these malicious applications have been coded for include all forms of digital platforms, and Android operating systems have been found to have been primary targets for fraud in mobile banking. (Gertz 2015).

Cyber-criminal activities cost approximately $400 billion across the world each year in financial losses and damages (Rayman 2014). Some of these crimes come from a few renowned hackers. Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev, alias“lucky12345” and “slavik”, is wanted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for his software applications ‘Zeus’ and ‘GameOver Zeus’, that compromises bank account access data (FBI 2017). His programs have resulted in more than $100 million in financial loss. In 2014 hacker Vladimir Drickman plead guilty to the theft of over 160 million credit cards. His crime resulted in approximately $300 million stolen from individual and corporate accounts (Voreacos 2015).

Cyber extortion is one of the most popular types of crime, due to the fee demanded to restore the hijacked computer network is normally cheaper than having the problem repaired, and faster, with less risk of losing customers, so companies are generally willing to pay the ransom (Gertz 2015). The devices in which these malicious applications have been coded for include all forms of digital platforms, and Android operating systems have been found to have been primary targets for fraud in mobile banking. (Gertz 2015).

Cyber-criminal activities cost approximately $400 billion across the world each year in financial losses and damages (Rayman 2014). Some of these crimes come from a few renowned hackers. Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev, alias“lucky12345” and “slavik”, is wanted by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for his software applications ‘Zeus’ and ‘GameOver Zeus’, that compromises bank account access data (FBI 2017). His programs have resulted in more than $100 million in financial loss. In 2014 hacker Vladimir Drickman plead guilty to the theft of over 160 million credit cards. His crime resulted in approximately $300 million stolen from individual and corporate accounts (Voreacos 2015).

According to JD Sherry, the vice president of Trend Micro Crime’s division of technology and solutions, Russia has access to “some of the most technologically advanced tools” in the field of cyber-crime (Rayman 2014). Beyond the theft of money, some of these malicious programs target the military. Due to the nature of the parties interested in military intelligence, these types of crimes are either funded by or orchestrated from a government institution. Cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike identified Android specific malware that had been installed on Ukrainian military devices. This malware was designed to allow remote access to the infected devices, and was linked to the software originating from the Russian region by its malware being a variant of X-Agent; a type of virus believed to have been created in Russia (Heller 2016). CrowdStrike was the investigating firm for Democratic National Committee (DNC) when it was hacked in 2016 by a code using a tool set called ‘Dukes’, in which evidence in the investigation of this malware set suggest that is also had been developed in Russia (Lipton 2016).

The Russian Cyber-crime Industry

In 2015 Interpol estimated that there were 20,000 residents in Russia who engaged in cyber-crime; primarily involving bank fraud, extortion, and email scams (Gertz 2015). Innovative in improving marketing techniques, some cyber criminals create their own websites. Russian and Ukrainian hackers created a website in 2001 called CarderPlanet. This website featured an e-Bay like market system for the purchase and sale of credit card numbers, complete with reviews, a message board, and paid advertising (Poulsen 2016).

Aside from credit card theft, a hacker can be commissioned to compromise a business network system with a cost range between $100 and $300 (Gertz 2015). Hackers also advertise to commit character assassination to an individual or business. The cost of flagging an individual as a child porn user, which will lead to their arrest and discredit their name, is $600 (Higgins 2016). When a hacker manages to successfully compromise a bank, their code becomes the most marketable item they have. Rather than take some money from the hacked bank and disappear, the code gets programmed into software that will automatically commit the hijack, and the hacker will sell that for around $3000 a copy (Poulsen 2016). In turn, those purchasers hire others to spam the software and money launderers. Sometimes, instead of having these hackers perform a solo project, then try to find a buyer, hackers will collaborate to complete the entire system. When the hackers form these criminal groups, everyone gets assigned specialized roles. These can include “creating malware, cracking into networks, handling security credentials, and laundering the proceeds of the crimes” (Gertz, 2015).

Aside from credit card theft, a hacker can be commissioned to compromise a business network system with a cost range between $100 and $300 (Gertz 2015). Hackers also advertise to commit character assassination to an individual or business. The cost of flagging an individual as a child porn user, which will lead to their arrest and discredit their name, is $600 (Higgins 2016). When a hacker manages to successfully compromise a bank, their code becomes the most marketable item they have. Rather than take some money from the hacked bank and disappear, the code gets programmed into software that will automatically commit the hijack, and the hacker will sell that for around $3000 a copy (Poulsen 2016). In turn, those purchasers hire others to spam the software and money launderers. Sometimes, instead of having these hackers perform a solo project, then try to find a buyer, hackers will collaborate to complete the entire system. When the hackers form these criminal groups, everyone gets assigned specialized roles. These can include “creating malware, cracking into networks, handling security credentials, and laundering the proceeds of the crimes” (Gertz, 2015).

While compromising bank security systems and acquiring credit card data are normally privately vested activities, there are cyber-crimes that are of greater interest to government agencies. Targeted character assassinations are seemingly popular within opposing Russian political parties (Higgins 2016). Hackers also target military, political, and other government systems. On March 15, 2017 the United States Justice Department charged 2 members of the ‘Federal’naya sluzhba bezopasnosti Rossiyskoi Federatsii’ (Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation)(FSB), and 2 Russian civilians of the hacking into over 500 million Yahoo accounts in 2014 (Nakashima 2017). The European Council on Foreign Relations has stated their suspicions that the FSB is responsible for many cyber-crimes against other government agencies. While the location of the attacks coming from the country of Russia is certain, it is currently unknown whether these attacks are managed by the government or commissioned to a third party hacker group. Also, due to the anonymity in which these attacks are generally carried out, obtaining proof of the source of these cyber-crimes has been extremely difficult (Galeotti 2016).

The Growth of Russian Cyber-crime

Cyber-crimes based in Russia have been increasing; both in occurrences and level of sophistication in the attacks (Gertz 2015). The correspondence to this allegation is represented in magnitude of funds that has been stolen in digital bank heists, and in cyber-attacks that utilize the same tool kit for their various hacking toolsets, like ‘Dukes’, which has been identified in ever evolving codes associated with hacker group APT29 since 2008 (Lehtiö 2015). Market growth also can been seen by business competition. Several years ago software Trojans targeting computer networks were sold for $250, but in 2015 similar programs decreased in price to $50 dollars (Gertz 2015).

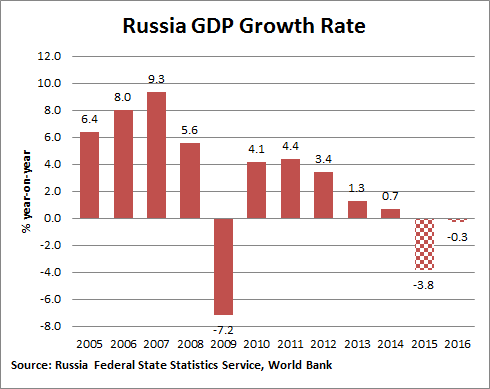

In 2015 Russia went into a recession, and the lack of well-paying legitimate jobs encouraged the engagement of illegal activities (Kottasova 2016). A 2015 FBI campaign targeting Russian hackers realized the financial motivation behind hacking, and were able to identify cyber-criminals by presenting them job opportunities at a fake company (Poulsen 2016). Through the use of encryption and anonymization tools like as Tor, the tracking of cyber-criminals is extremely difficult. Hacker groups set up various offices in different countries, and remove proof of their illegal activities once their job is done (Gertz 2015). There is also a low rate of prosecution and punishment for those who do get arrested for hacking. When credit card number thief alias ‘Script’ was arrested in the Ukraine for selling stolen numbers to an FBI sting in the United States, Ukraine tried him instead of extraditing him to the United States. For his conviction, he was sentences to six months jail time (Poulsen 2016).

The Russian constitution disallows the extradition of its citizens for criminal processing (Harding 2007). That means that Russian hackers who commit crimes against institutions outside of their country will not be tried. For those who get caught committing a cyber-crime in Russia, the FSB may exchange legal charges for time served working for the FSB (Nakashima 2017). Those hacker groups commissioned by the Russian government also experience even more security while committing their crimes (Lehtiö 2015).

Analysis and Conclusion

In 2015 Russia went into a recession, and the lack of well-paying legitimate jobs encouraged the engagement of illegal activities (Kottasova 2016). A 2015 FBI campaign targeting Russian hackers realized the financial motivation behind hacking, and were able to identify cyber-criminals by presenting them job opportunities at a fake company (Poulsen 2016). Through the use of encryption and anonymization tools like as Tor, the tracking of cyber-criminals is extremely difficult. Hacker groups set up various offices in different countries, and remove proof of their illegal activities once their job is done (Gertz 2015). There is also a low rate of prosecution and punishment for those who do get arrested for hacking. When credit card number thief alias ‘Script’ was arrested in the Ukraine for selling stolen numbers to an FBI sting in the United States, Ukraine tried him instead of extraditing him to the United States. For his conviction, he was sentences to six months jail time (Poulsen 2016).

The Russian constitution disallows the extradition of its citizens for criminal processing (Harding 2007). That means that Russian hackers who commit crimes against institutions outside of their country will not be tried. For those who get caught committing a cyber-crime in Russia, the FSB may exchange legal charges for time served working for the FSB (Nakashima 2017). Those hacker groups commissioned by the Russian government also experience even more security while committing their crimes (Lehtiö 2015).

Analysis and Conclusion

Russia is home to hackers who engage in many different types of cyber-crimes; most prominently money and intelligence gathering. Tracking and convicting cyber-criminals is extremely difficult, and those who do get convicted abroad serve generally small sentences. While the United States has put harsher sentences on the criminals it convicts, not all countries are willing to extradite the Russian hackers they arrest. If anything, the identification of some of these criminals who reside in Russia gives the FSB the ability to track and recruit them for their own means. As the Russian government still struggles to get out of its recession, civilian hackers will continue to commit digital fraud for their means of income. There will also be a continued use of government operated or contracted hackers for their intelligence gathering goals.

Works Cited

FBI (2017) Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev. Retrieved from https://www.fbi.gov/wanted/cyber/evgeniy-mikhailovich-bogachev

Galeotti, Mark (May 2016). PUTIN’S HYDRA: INSIDE RUSSIA’S INTELLIGENCE SERVICES. European Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved from http://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/ECFR_169_-_PUTINS_HYDRA_INSIDE_THE_RUSSIAN_INTELLIGENCE_SERVICES_1513.pdf

Gertz, Bill (October 2 2015). Interpol: Cyber Crime from Russia, E. Europe Expands. The Washington Free Beacon. Retrieved from http://freebeacon.com/national-security/interpol-cyber-crime-from-russia-e-europe-expands/

Harding, Luke (May 22 2007). Russian law prevents extradition. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/may/22/russia.lukeharding

Kottova, Ivana (Aug 11 2016). Russia’s economy has been in recession for 18 months. CNN. Retrieved from http://money.cnn.com/2016/08/11/news/economy/russia-economy-recession-six-quarters/

Kramer, Andrew (Apr 9 2017). Spain Arrests Russian Thought to Be Kingpin of Computer Spam. The New York Times. Retrieved https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/09/world/europe/peter-severa-levahsov-russia-arrest.html?_r=0

Lehtiö, Artturi (Sep 17 2015). The Dukes: 7 Years Of Russian Cyber-Espionage. F-Secure. Retrieved from https://www.f-secure.com/documents/996508/1030745/dukes_whitepaper.pdf

Lipton, E., Sanger, G. & Shane S. (DEC. 13, 2016). The Perfect Weapon: How Russian Cyberpower Invaded the U.S. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/13/us/politics/russia-hack-election-dnc.html

Heller, Michael (Dec 22 2016) Fancy Bear ties to Kremlin strengthened with Ukraine military hack. SearchSecurity. Retrieved from http://searchsecurity.techtarget.com/news/450409947/Fancy-Bear-ties-to-Kremlin-strengthened-with-Ukraine-military-hack

Higgin, Andrew (Dec 9 2016). Foes of Russia Say Child Pornography Is Planted to Ruin Them. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/09/world/europe/vladimir-putin-russia-fake-news-hacking-cybersecurity.html

Nakashima, Ellen (Mar 15 2017). Justice Department charges Russian spies and criminal hackers in Yahoo intrusion. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/justice-department-charging-russian-spies-and-criminal-hackers-for-yahoo-intrusion/2017/03/15/64b98e32-0911-11e7-93dc-00f9bdd74ed1_story.html?utm_term=.d94f08f1d3ad

Poulsen, Kevin (May 2016). The Ukrainian Hacker who became the FBI’s best Weapon – and worst Nightmare. Wired. Retrieved from https://www.wired.com/2016/05/maksym-igor-popov-fbi/

Rayman, Noah (Aug 7 2014) The World’s Top 5 Cybercrime Hotspots. Time. Retrieved from http://time.com/3087768/the-worlds-5-cybercrime-hotspots/

Voreacos, David (Sept 15 2015). Russian Hacker Pleads Guilty in Largest Data Breach. Bloomberg Technology. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-09-15/russian-hacker-drinkman-pleads-guilty-in-largest-data-breach-ielr56e4